Learning Objectives

Categorize data file formats

Data Storage Formats#

The power and utility of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) largely depend on the ability to effectively store, retrieve, and process spatial data. As such, understanding the various data storage formats is essential for anyone working in the GIS domain. The chosen format can significantly influence the ease of data manipulation, the efficiency of spatial queries, and the compatibility of data with various software systems.

In this guide, we will explore a variety of storage formats used for vector and raster data types in GIS. We will begin with vector data formats such as GeoJSON, GeoPackage, Shapefile, and File Geodatabase. Each of these formats offers unique advantages and disadvantages in terms of readability, data compactness, and compatibility with different software applications.

After discussing vector formats, we will then shift our focus to raster data storage. We will talk about the role of pixel depth in defining raster data and explore popular raster file formats, including Imagine, GeoTiff, and File Geodatabase.

By understanding these formats, you can make informed decisions about the most suitable data storage strategy for your specific GIS project. Let’s get started!

Vector Data File Formats#

GeoJSON#

GeoJSON is an open standard format specifically designed for representing simple geographical features, along with their non-spatial attributes, based on JavaScript Object Notation (JSON). It can accommodate diverse types of geographical features such as points, line strings, polygons, and multi-part collections of these types. One of its primary advantages is its readability - both by humans and machines, as it stores all the relevant data in a single text file. However, this advantage could turn into a disadvantage when dealing with intricate geometries, leading to significantly large file sizes.

To illustrate, here’s an example of a GeoJSON feature collection. This particular collection includes three features: a point, a line string, and a polygon. Each feature is characterized by two primary components: geometry and properties.

The

geometrydescribes the spatial characteristics of the feature. For instance, the point is defined by its coordinates [102.0, 0.5].The

propertiesobject is where non-spatial information or attributes related to the feature are stored. These properties can be anything from simple key-value pairs (like “prop0”: “value0”) to more complex structures.

{

"type": "FeatureCollection",

"features": [

{

"type": "Feature",

"geometry": {

"type": "Point",

"coordinates": [102.0, 0.5]

},

"properties": {

"prop0": "value0"

}

},

{

"type": "Feature",

"geometry": {

"type": "LineString",

"coordinates": [

[102.0, 0.0], [103.0, 1.0], [104.0, 0.0], [105.0, 1.0]

]

},

"properties": {

"prop0": "value0",

"prop1": 0.0

}

},

{

"type": "Feature",

"geometry": {

"type": "Polygon",

"coordinates": [

[ [100.0, 0.0], [101.0, 0.0], [101.0, 1.0], [100.0, 1.0], [100.0, 0.0] ]

]

},

"properties": {

"prop0": "value0",

"prop1": {

"this": "that"

}

}

}

]

}

In this example, the spatial data is stored in the geometry attribute, and additional properties related to each feature are stored in the properties attribute. As such, GeoJSON format allows for a comprehensive and flexible representation of geospatial data.

GeoPackage#

GeoPackage is a modern, open standard data format that adopts the principles of open format standards, ensuring non-proprietary access and wide compatibility. It leverages SQLite, a widely used, self-contained, and serverless transactional SQL database engine, making it an exceptionally portable and lightweight choice for data storage.

A key benefit of the GeoPackage format is its impressive compactness. All necessary geospatial data components, including coordinate values, metadata, attribute tables, and projection information, are consolidated into a single file. This file typically bears a .gpkg extension. The compact nature of GeoPackage not only simplifies data management but also greatly enhances data portability. You can easily move, share, or archive your geospatial data, which can be a significant advantage in collaborative and dynamic project environments.

Another important advantage of GeoPackage is its wide software compatibility. Prominent GIS and data analysis applications like QGIS (versions 2.12 and up), R programming language, and ArcGIS readily support this format. While ArcGIS version 10.2.2 and above can read GeoPackage files from ArcCatalog, creating a GeoPackage might require a specific script.

Furthermore, as GeoPackage is a relatively new format, it is designed with current and evolving geospatial industry practices and standards in mind. This makes it a future-proof choice that can readily handle modern geospatial data complexities.

Shapefile#

A Shapefile is a prevalent, file-based data format that was originally associated with ArcView 3.x software, a predecessor to the modern ArcMap and ArcGIS. In essence, a shapefile is akin to a feature class – it stores a set of features that share a common geometry type (point, line, or polygon), possess the same attributes, and occupy a shared spatial extent.

Contrary to what the term ‘shapefile’ suggests, it doesn’t correspond to a singular file. Rather, a shapefile is an assembly of at least three separate files and can include up to eight or more. Each constituent file within a “shapefile” ensemble shares the same base filename but differs in its extension type, indicating its unique role in the shapefile structure.

The following table outlines the different file extensions found in a shapefile and the specific type of content each file carries:

File extension |

Content |

|---|---|

.dbf |

Attribute information |

.shp |

Feature geometry |

.shx |

Feature geometry index |

.aih |

Attribute index |

.ain |

Attribute index |

.prj |

Coordinate system information |

.sbn |

Spatial index file |

.sbx |

Spatial index file |

Each file extension serves a distinct purpose in the overall shapefile structure. For example, the .shp file houses the geometric data of the features, while the .dbf file contains the attribute information for each feature. The multiple-file structure of a shapefile thus allows for a comprehensive representation of geospatial data, although it can make file management more complex compared to formats that encapsulate all data within a single file.

File Geodatabase#

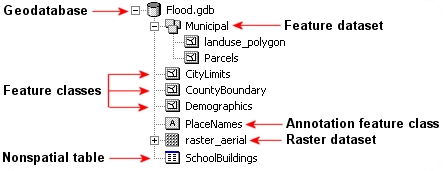

A File Geodatabase is a sophisticated form of a relational database designed for storing geospatial data. Compared to a shapefile, a file geodatabase employs a much more intricate data structure, encapsulated within a single .gdb folder. However, don’t let the singular folder fool you - inside it, there are potentially dozens of different files, each playing a part in storing and organizing your geospatial data.

The primary advantage of a file geodatabase is its flexibility and capacity. It can house multiple feature classes - such as points, lines, and polygons - each with their own set of attributes. Additionally, it supports topological definitions, enabling users to establish and enforce rules about the relationships between different feature classes. This versatility makes file geodatabases a preferred choice for complex projects involving varied types of geospatial data and intricate inter-feature relationships.

Below is an illustrative representation of a file geodatabase’s contents. You can see how it organizes multiple types of data into a cohesive structure, allowing for efficient storage and retrieval of geospatial data.

Fig. 19 A geodatabase#

In the figure above, the File Geodatabase is visually represented, highlighting its ability to cohesively organize various forms of geospatial data and related metadata within a single, unified structure.

Raster Data File Formats#

While vector data represents discrete geographical features like points, lines, and polygons, Raster data provides a more continuous perspective. It consists of a matrix of cells, or pixels, each with a specific value that represents a particular characteristic of that area, such as elevation, temperature, or land cover type. This pixel-based structure makes raster data particularly suitable for representing large, continuous surfaces and gradual transitions in attribute values.

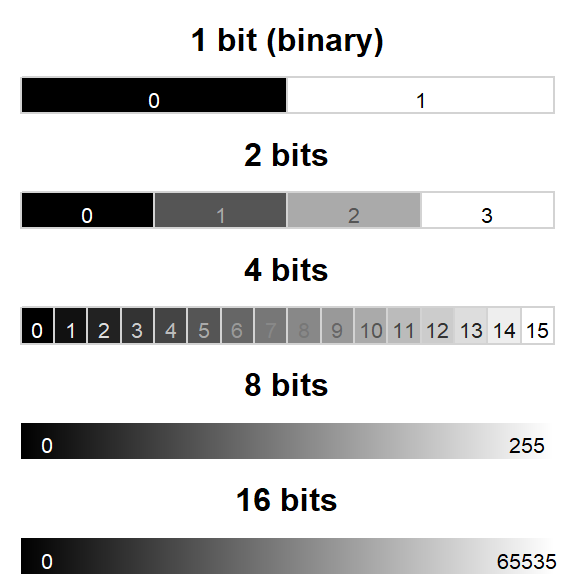

An essential aspect of raster data is pixel depth. Pixel depth refers to the range of distinct values that a pixel in the raster can store. For example, a 1-bit raster can only store two distinct values: 0 and 1. This range expands as the pixel depth increases, allowing for a more nuanced representation of data, but it also requires more storage space.

Fig. 20 Pixel depth allows for a wider range of values but also takes up more space#

A variety of raster file formats are used in the realm of Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Below, we delve into some of the most popular ones.

You can learn more about raster data in our section on Raster Data Introduction.

Imagine#

The Imagine file format, developed by the image processing software company ERDAS, is a straightforward format represented by a single .img file. It is simpler than the shapefile format and often comes with an associated .xml file, which typically contains metadata about the raster layer.

GeoTiff#

GeoTIFF is a widely-used raster data format in the public domain. It is a great choice when you prioritize portability and platform independence as it embeds spatial information within the TIFF image file itself.

File Geodatabase#

Raster data can also be stored in a File Geodatabase, alongside vector data. File Geodatabases offer certain advantages for handling raster data. They can define image mosaic structures, allowing users to “stitch” together multiple image files stored in the geodatabase. Furthermore, processing extensive raster files can be computationally more efficient in a File Geodatabase, compared to an Imagine or GeoTiff file format.

Learn More#

For a deeper understanding of geospatial data storage formats, consider the following resources:

Books:

GIS: A Computing Perspective: This book offers a full, comprehensive overview of GIS from a computer science viewpoint, covering spatial data modeling, data structures, and algorithms.

Designing Geodatabases: Case Studies in GIS Data Modeling: This book introduces the concept of a geodatabase, which is a more sophisticated way of organizing spatial data than the traditional shapefile.

Online Resources:

GDAL Documentation: Comprehensive guide and API reference for GDAL (Geospatial Data Abstraction Library), a translator library for raster and vector geospatial data formats.

A brief history of the geodatabase: This blog series and explains the evolution of geodatabases.

The GeoJSON Format Specification: This is the official website for the GeoJSON format, offering a detailed specification and examples.